Strengthening Identity to Make Dreams Come True

February 19, 2026Synergy and Innovation: HIV and AIDS Control Integrated Control Journey

The presence of AIDS Care Communities, People Living with HIV (PLHIV) Community, Village Government, Subdistrict Head, Community Health Centre, Hospital, AIDS Commission and Health Office in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality that support each other and synergise has resulted in higher quality health services and improved the quality of life of PLHIV.

It is no exaggeration to say that, over nearly three years of implementing the Integrated HIV and AIDS Control Program (2022–2025) in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality, CD Bethesda YAKKUM has achieved significant milestones and made substantial contributions. These efforts have supported the realisation of an integrated HIV prevention program and improved the health and quality of life for people living with HIV (PLHIV) and those affected by it in both regions.

Efforts have been made to improve access to health services, strengthen mentoring systems for PLHIV, and optimise local budget allocations. e program has demonstrated significant achievements across various areas. However, challenges remain, including expanding the number of health facilities providing comprehensive HIV services, improving adherence to Antiretroviral (ARV) medication, and fostering active community involvement in supporting HIV and AIDS control initiatives. The implementation of comprehensive services refers to the provisions of the Indonesian Ministry of Health, which include all forms of HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) services, encompassing promotional, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative efforts. These comprehensive services are provided continuously or comprehensively, starting from the home or community, to health facilities such as community health centres, clinics, and hospitals, and returning to the home or community. Services are provided throughout the HIV infection, from pre-infection to the terminal stage. Meanwhile, efforts to improve ARV adherence among PLHIV are intended to eliminate cases of Lost to Follow-Up (LFU) or discontinuation of medication to prevent deaths due to AIDS. This means that through ARV adherence, PLHIV can continue their lives with good health. In addition to increasing the number of service locations for Care, Support, and Treatment (CST) through the implementation of Continuum of Care Service at health centres and hospitals, community involvement through AIDS care community and peer support groups is also a serious concern in HIV and AIDS control.¹

Program Relevance

The Integrated HIV and AIDS Control program in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality is still relevant to the needs of key populations and vulnerable groups. The implementation of the program is in line with national policies in HIV and AIDS response, including:

Minister of Health Regulation No. 23 Year 2022 on HIV, AIDS, and Sexually Transmitted Infections Management which regulates service standards and national strategies in HIV control.

This regulation establishes service standards that include the implementation of health education and promotion to increase public awareness on HIV and STI prevention, provision of accessible and confidential HIV counselling and testing services for early detection of infection, provision of ARV therapy for PLHIV and treatment for people with STIs by national guidelines. The policy also stipulates the importance of providing laboratory facilities capable of conducting HIV and STI testing with established quality standards, as well as strengthening referral systems and psychosocial support for PLHIV and people with STIS to ensure continuity of care. The national strategy for HIV and AIDS control, as outlined in this regulation, includes several key components: increasing the involvement of the government and other stakeholders in HIV and STI prevention efforts; ensuring the availability and affordability of prevention, treatment, and care services for all segments of society, including vulnerable groups; reducing risk factors for HIV and STI transmission through effective interventions; enhancing the capacity of health workers and relevant personnel to deliver quality services; and conducting regular monitoring and evaluation to assess the effectiveness of implemented programs and policies. The regulation also highlights the critical importance of collaboration among the government, private sector, and communities in delivering a comprehensive response to HIV, AIDS, and STIs.²

The 2020-2024 National Strategy and Action Plan emphasises increased access to HIV treatment and prevention services.

The policy is designed to achieve the 95-95-95 global targets, which are: 95% of PLHIV know their HIV status, 95% of those diagnosed with HIV receive ongoing ART, 95% of those on ART achieve viral load suppression. Several key strategies are in place to increase access to HIV treatment and prevention services to achieve these targets, including:

-

Scaling up HIV Counselling and Testing Services: expanding access to integrated HIV counselling and testing services in health facilities and communities for early detection.

-

Improving Access and Quality of ARV Therapy: ensuring equitable availability and distribution of ARVs throughout the region and increasing the capacity of health workers in ARV therapy management.

-

Strengthening Referral Systems and Integrated Services: integrating HIV services with other health programs, such as tuberculosis and reproductive health, to facilitate access to comprehensive services.

-

Community and Key Population Empowerment: increasing community participation in education, prevention, and assistance of PLHIV.

-

Strengthening Information and Monitoring Systems: developing a reliable information system for regular program monitoring and evaluation.

-

Stigma and Discrimination Reduction: Conduct educational campaigns to reduce stigma and discrimination against PLHIV.

Implementing these strategies is expected to improve access to and quality of HIV prevention and treatment services in Indonesia, in line with the targets set in the 2020-2024 Strategic Plan.³ Some of the program achievements that demonstrate its relevance to the needs of key populations and vulnerable groups are as follows:

First, the existence of the AIDS Care Community as a partner of CD Bethesda YAKKUM can become a driving force for HIV and AIDS control efforts in the community by advocating for HIV and AIDS program budgeting policies in villages and sub-districts, educating the community and providing assistance to PLHIV. AIDS Care Community, according to the Indonesian Ministry of Health, is a forum for community participation in the HIV and AIDS Response.⁴

Secondly, program support for Yogyakarta Kebaya Foundation is relevant to institutional management, capacity building of members, and policy advocacy. The cooperation between CD Bethesda YAKKUM and Yogyakarta Kebaya Foundation up to semester 5 has occurred through collaboration, facilitation, and regular provision of assistance. Some collaborations recorded include: Shelter SOP Review, Oil Massage Making Training, Massage Coaching, Local Food Coaching, Preparing Institutional SOPs and Preparing the Strategic Plan of Yogyakarta Kebaya Foundation.

Third, the Integrated HIV and AIDS Control program is also relevant to the needs of the Health Office to maintain commitment and policies related to HIV and AIDS through the regional action plan for HIV and AIDS Response. A regional action plan requires attention and regular supervision to achieve maximum results. CD Bethesda YAKKUM and the network also actively participated in this joint process, even in the monitoring process. A regional action plan is a guideline developed by many cross-sector parties involved. Therefore, each institution, community, or Local Government Department is also committed to overseeing this process.

Fourth, the Integrated HIV and AIDS Control Program aligns with the needs of the Belu Regency AIDS Commission, particularly in its continued support for AIDS care communities at the village level. Following a structural reorganisation, the Belu Regency AIDS Commission has gradually begun to optimise its role in HIV and AIDS control efforts.

Program Effectiveness

The Integrated HIV and AIDS Control program in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality is adequate because it has achieved the set indicators. Based on the indicators in the framework, some of the main achievements of the Integrated HIV and AIDS Control program include:

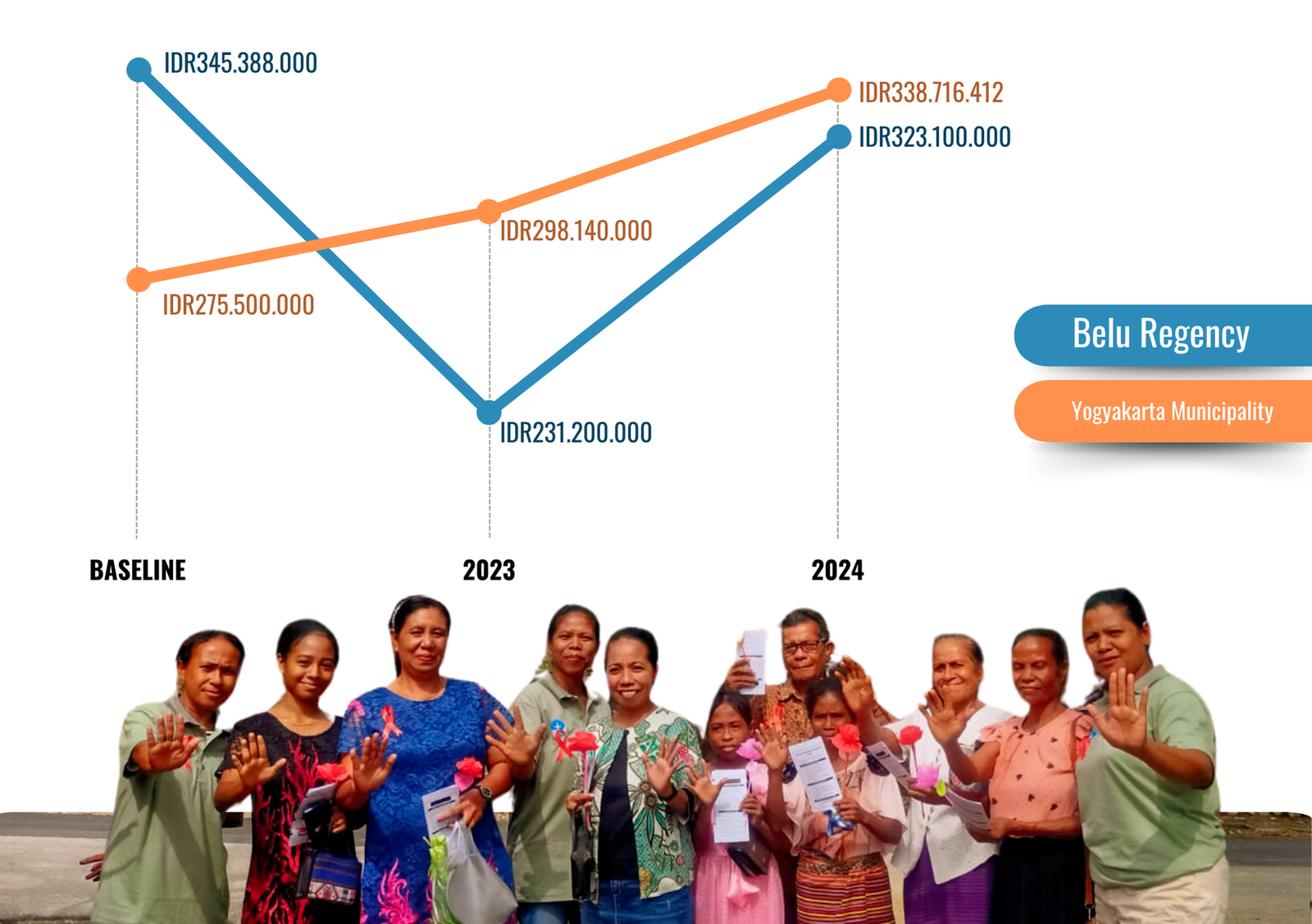

Local budget allocations for HIV and AIDS control programs in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality in 2024 increased by an average of 6.6% compared to the baseline.

In 2024, the budget allocation for Belu Regency is Rp323,100,000, representing a 6.5% decrease from the 2021 baseline of Rp345,388,000. This funding supports services for PLHIV, AIDS care communities, high-risk groups, cross-sector coordination, and the operational needs of the AIDS Commission. In contrast, Yogyakarta Municipality’s 2024 budget allocation is IDR338,716,412—a 23% increase from the 2021 baseline of IDR 275,500,000. This allocation supports various activities, including coordination of HIV service networks, capacity building for HIV service providers, updated knowledge on hepatitis and TB prevention in PLHIV, validation of HIV and AIDS data, monitoring and evaluation of the Regional Action Plan, World AIDS Day commemorations, refresher training for HIV and STI analysts, and the integration of HIV activities into broader health initiatives.

Twelve health providers—comprising four hospitals and eight health centres—and 15 health services have implemented the HIV Continuum of Care following the standards set by the Indonesian Ministry of Health. This achievement surpasses the initial program target of nine health services

In Belu Regency, six health services are implementing the HIV Continuum of Care, which consists of two hospitals—Atambua Regional Public Hospital and Marianum Halilulik Hospital—and four health centres: Atapupu, Wedomu, South Atambua, and Umanen Public Health Centres. Similarly, six health services in Yogyakarta City provide the HIV Continuum of Care. These include two hospitals—Yogyakarta City Hospital and Bethesda Hospital—and four public health centres: Gedongtengen, Umbulharjo 1, Tegalrejo, and Mantrijeron.

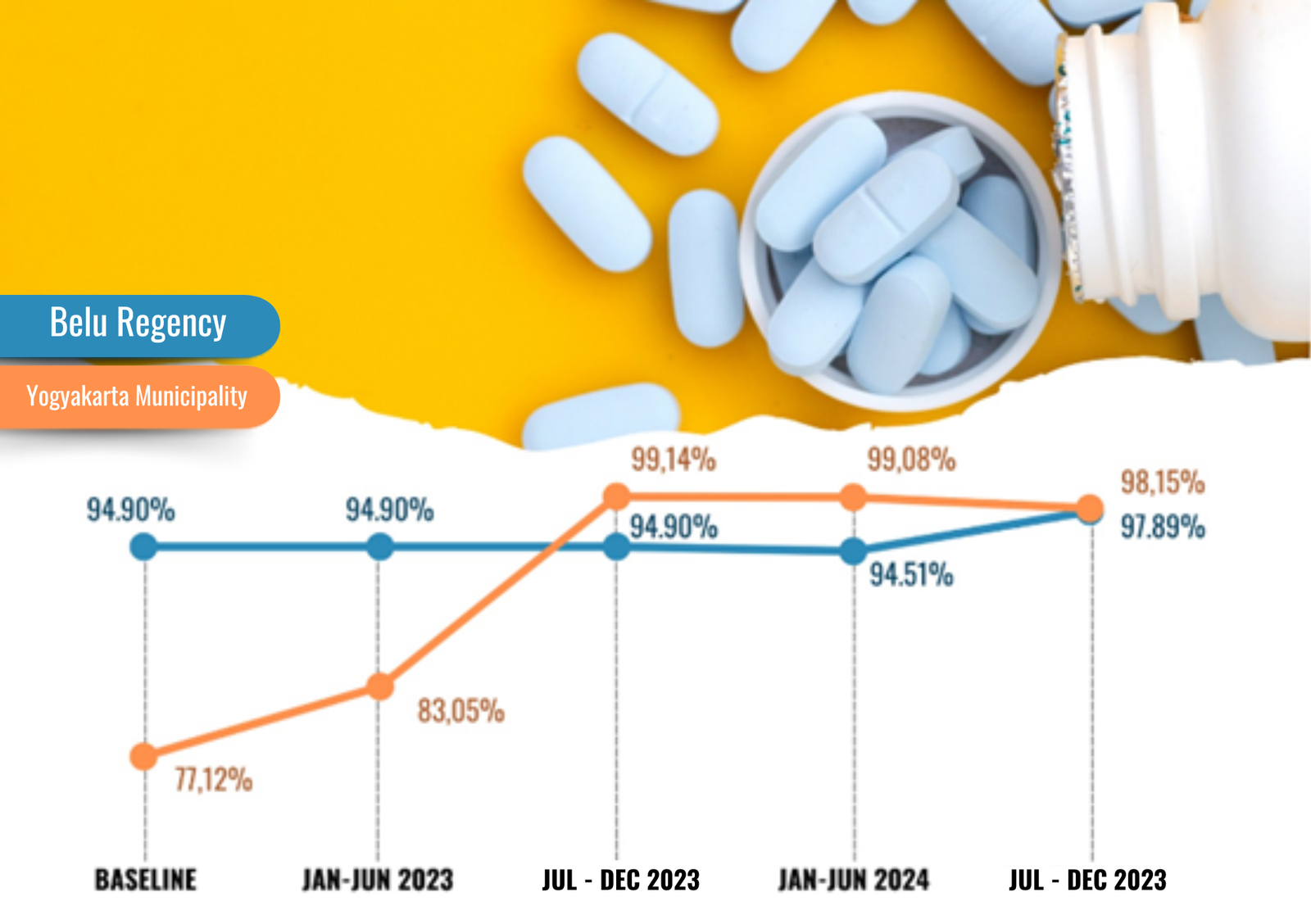

The HIV and AIDS Control program, which also seeks to improve drug adherence, recorded that 98.03% of PLHIV assisted were taking ARVs regularly.

Based on the data, of the 203 PLHIV assisted, comprising 129 men, 67 women, and seven transgender individuals, 199 (125 men, 67 women, and seven transgender individuals), or 98.03%, are routinely taking antiretroviral (ARV) medication. This exceeds the program target of 70%. However, four male PLHIV (1.97%) are classified as lost to follow-up (LFU). In the Belu Regency, out of 95 PLHIV assisted (43 men, 51 women, and one transgender person), 93 (41 men, 51 women, and one transgender person) are adhering to ARV treatment, while two male PLHIV are LFU. In Yogyakarta City, of the 108 PLHIV supported (86 men, 16 women, and six transgender individuals), 106 (84 men, 16 women, and six transgender individuals) are taking ARVs regularly, with two male PLHIV reported as LFU.

Partner village governments have increased budget allocations for HIV and AIDS

prevention programs focused on vulnerable groups. The budget for HIV and AIDS

issues in the 16 villages served increased by almost four thousand per cent

(3,790%) from Rp5,472,556 to a total of Rp212,842,120.

Partner village governments have increased budget allocations for HIV and AIDS prevention programs focused on vulnerable groups. The budget for HIV and AIDS issues in the 16 villages served increased by almost four thousand per cent (3,790%) from Rp5,472,556 to a total of Rp212,842,120.

- In the Belu Regency, eight assisted villages have allocated a budget of IDR 132,049,900 for HIV and AIDS programs focusing on vulnerable groups of PLHIV

and housewives. In Yogyakarta City, eight assisted villages have allocated budgets of IDR80,792,220 for HIV and AIDS programs focused on vulnerable groups of Youth, Housewives, Tuberculosis patients, and STI patients 20. A total of 4 Peer Support Groups formed at the end of the project’s first phase continue to assist PLHIV and people who live with HIV independently without the support of CD Bethesda YAKKUM. The peer support group is a group that aims to support each member of the group in their daily lives.⁵ Peer support includes people who face the same challenges, such as patients with certain infections or specific communities. In Yogyakarta City, the peer support group that was formed at the end of the first phase of the project (Pita Merah Jogja Association) is preparing to be able to continue its activities beyond the support of CD Bethesda YAKKUM through: establishment of legality from Ministry of Law and Human Rights as a community organisation under the name Pita Merah Jogja Association, implementation of a fundraising mechanism from deductions of honorarium for resource persons from other parties and voluntary contributions from members, funding from outside parties, namely from the YAKKUM Emergency Unit (YEU) to develop the PLHIV Health Monitoring application (MONTOV), funding from outside parties, namely the Bethesda Hospital Inclusion Program to conduct MONTOV socialisation for PLHIV who access services at Bethesda Hospital and development of group economic businesses through the sale of merchandise such as t-shirts, mugs, tumblers, pins, and key chains. A total of 3 peer support groups in Belu Regency, formed at the end of the first phase of the project, have made preparations for independence to continue assisting PLHIV 5 and people who live with PLHIV, with details: - One peer support group formed at the end of the first phase of the project at the regent level (Moris Foun Belu) has been taking care of the organisation’s legality, implementing a fundraising mechanism from deductions from resource persons’ honorariums, and developing group economic businesses in the form of selling herbal oils.

- Two peer support groups formed at the end of the project’s first phase at the subdistrict level (Kakuluk Mesak and East Tasifeto) have developed group economic businesses in the production of herbal oils and instant herbal products.

Program Efficiency Level

The Integrated HIV and AIDS Control program optimised the resources available in the program area through the involvement of the community and relevant stakeholders, making its implementation efficient.

Advocacy for the integration of the HIV budget with other health issues, such as maternal and child health, tuberculosis, and STIs, in the Health Office due to limited budget allocation specifically for HIV and AIDS programs.

This integrated approach enables the HIV program to receive broader budgetary support and establishes direct linkages with other health services. Beyond improving the efficiency of health fund utilization, the integration offers several key benefits: avoiding duplication of funding, facilitating community access to comprehensive health services, accelerating the detection and treatment of vulnerable groups in need of HIV, TB, STI, and maternal and child health services, and enhancing the overall effectiveness of health programs. This approach not only promotes the sustainability of HIV interventions but also contributes to improving the overall quality of health services.⁶

One of the program's achievements is building the capacity of health workers and other support groups to increase the number of PLHIV-friendly services.

Improving the capacity of health workers and peer support groups in the HIV and AIDS Control program results in improved service quality and contributes to overall program efficiency. This efficiency is achieved through optimising resources, reducing the burden of follow-up health services, and enhancing PLHIV’s adherence to treatment and care. Increased capacity of health workers also creates more effective and efficient services. With more health workers trained in HIV services, PLHIV do not always need to be referred to large hospitals and can receive care directly at health centres, reducing waiting times and operational burden on secondary health facilities.⁷ Peer support groups are crucial in improving treatment adherence and accelerating access to services, contributing to overall program efficiency. Mentoring activities help PLHIV remain consistent in taking ARV medication, which reduces the risk of health complications and minimises the need for more intensive medical care. This, in turn, is expected to lower the costs associated with treating complications or opportunistic infections, allowing health programs to focus more on preventive efforts. Trained peer support groups also facilitate faster and more cost-effective dissemination of HIV-related information at the community level, reducing reliance on health professionals. Their educational efforts help dispel misconceptions and reduce stigma, encouraging more individuals to seek HIV testing and treatment earlier.⁸

Increased community engagement, such as AIDS care community and peer support group, to support advocacy at the local level

Community involvement in HIV and AIDS control programmes is essential for improving their effectiveness and efficiency. AIDS care communities and peer support groups play a strategic role in local advocacy by helping to bridge access to health services and optimise available resources. An AIDS care community is a local group that contributes to HIV and AIDS education within its neighbourhood. These groups help reduce stigma and discrimination, encouraging more PLHIV to access health services without fear. In addition, AIDS care communities work with local authorities to advocate for the allocation of village or sub-district budgets to support HIV and AIDS services. Their involvement in the Share, Support, Stimulate, Appreciate, Analyse, Learn, Listen, Link, Team, Transfer (SALT) process—as well as in the formulation of SALT visit outcomes discussed in hamlet or village meetings involving village and sub-district authorities—is considered adequate. The program proposals require community participation and are tailored to local needs, allowing village and sub-district authorities to incorporate them into local development plans. A peer support group consists of PLHIV who provide social and emotional support to one another. They play a role in assisting PLHIV to remain compliant with ARV therapy, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the treatment programme. Peer support groups also help PLHIV access health services and local policy advocacy, including providing ARV and comprehensive services.⁹

Program Impact

The impact of the Integrated HIV and AIDS Control Program in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality is evident across several areas. From a policy perspective, it is reflected in developing the Regional Action Plan for the HIV and AIDS Response. From a health service perspective, it includes the implementation of HIV continuum-of-care services and STI services, which have led to improved access to care for PLHIV. There has also been an increase in the active involvement of village governments and communities in supporting HIV and AIDS prevention programs, along with a reduction in stigma towards PLHIV.

In terms of policy, one impact of the program implementation was the development of regional action plan documents on HIV and AIDS response in the Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality.

This document is the basis that HIV and AIDS control efforts need to be supported by cross-sectoral involvement. The issue of HIV and AIDS will not be solved by the Health Office alone. It requires the support of other regional apparatus organisations in promotional efforts so that more people have a correct understanding of HIV and AIDS. Collaboration between the government, community organisations, and the health sector is essential in improving PLHIV’s access to services. Effective coordination can strengthen HIV and AIDS response efforts, improve service quality, and ensure targeted policy implementation.

In terms of health services, the implementation of HIV and STI CSOs at the regency level aims to provide comprehensive services.

These efforts are expected to reduce morbidity, mortality, and discrimination while improving the quality of life for PLHIV. Broader and higher-quality service coverage has made it easier and more efficient for PLHIV to access health services. As a further impact of the HIV- and STI-friendly continuum of care approach, the programme has contributed to the initiation of HIV-friendly service monitoring tools, developed collaboratively by the Health Office, health service providers, and community representatives. These tools will enable health services in the Belu Regency and the Yogyakarta Municipality to conduct independent monitoring and ensure the delivery of HIV-friendly care. Following the development of the monitoring tools, health workers in various health facilities were trained on PLHIV-friendly services. The implementation of a continuum of care service monitoring tools has reduced discriminatory attitudes that previously discouraged PLHIV from seeking care. The existence of a code of ethics for inclusive services has made health workers more aware of the rights of PLHIV and ensured non-discriminatory services. Community health centres have begun to provide more private and comfortable service areas for PLHIV, so they do not feel judged or overly monitored when accessing health services.¹⁰

Another impact of program implementation is the active involvement of villages and communities in supporting HIV and AIDS programs

A total of 16 villages have allocated budgets to support HIV and AIDS programs, such as HIV and AIDS education, AIDS care, community transport and direct assistance for PLHIV. AIDS care communities in all villages have started to play a role in HIV prevention education and advocacy. The cadre conducts education about HIV and AIDS, facilitates voluntary testing, and supports PLHIV in accessing health services. Peer support group plays a role in supporting PLHIV psychosocially, assisting them in adherence to ARV therapy, and reducing the stigma they face. This community also helps in encouraging PLHIV who have not started ARV therapy to access health services immediately. Religious leaders and community leaders in several areas of Belu Regency have begun to engage in HIV education, changing the negative stigma that has developed in the community. They provide an understanding that PLHIV deserves fair treatment and social support. On the other hand, community-based campaigns have helped improve community understanding of HIV and AIDS. People are beginning to realise the importance of early HIV testing, condom use, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT).

Another visible impact of the HIV and AIDS control program is the reduction of stigma towards PLHIV

The stigma that has hindered access to health services has begun to diminish as community education and the provision of health services that are more inclusive and welcoming to PLHIV have increased. Community-based education programs provide correct information about HIV and AIDS, especially about the mode of transmission and the fact that HIV cannot be transmitted through touching, sharing cutlery, or ordinary social interactions. Community-based campaigns help dispel myths and exaggerated fears that lead to discrimination against PLHIV. The involvement of community leaders, religious leaders, and local leaders in anti stigma campaigns helps change community attitudes towards PLHIV. HIV education in the education sector is starting to be incorporated into school programs, especially in reproductive health and sexuality education. Students are taught not to discriminate against PLHIV, so that the younger generation grows up with a more inclusive understanding.

A further impact of the program is increased access to services for people living with HIV, including those living in border areas

These efforts ensure that all individuals have equal access to necessary health services regardless of geographical location. The increase in the number of health centres and hospitals that provide Care, Support, and Treatment (CST) services in border areas, such as Belu Regency, which borders Timor Leste, has facilitated access to health services for PLHIV. This allows PLHIV in the area to get the care they need without travelling far to the city centre. About the HIV and AIDS response at the border of Indonesia and Timor Leste, the program has also been able to initiate an Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that will soon be signed between the AIDS Commission of East Nusa Tenggara Province and the Instituto Nacional de Combate ao HIV-SIDA (INCSIDA) of East Timor to regulate the importance of HIV and AIDS education in border areas and CST referral networks for PLHIV between the two countries.

Program Sustainability

One of the important factors in the sustainability of the HIV and AIDS integrated control program is the budget allocation in the village fund.

This step enables villages to play a more active role in HIV and AIDS prevention and control at the community level, so programmes do not depend solely on the central government budget. To support programme sustainability, the Regent of Belu issued a circular requiring all villages to allocate Village Funds to support HIV and AIDS programmes. The Regent’s circular allows Village Funds to be allocated to programme partner villages and villages outside the programme intervention area. Several villages have begun to include HIV and AIDS as one of their priority programmes in the village development planning meeting. This positive development enables HIV programmes to receive official budget support from Village Funds, such as HIV prevention education in the community, facilitating free HIV testing for residents, or training for health cadres. The inclusion of HIV programmes in village budgets enables villages to take responsibility for supporting the sustainability of HIV and AIDS control programmes that have been collaboratively implemented with CD Bethesda YAKKUM. The existence of HIV programmes managed directly by villages has led to greater awareness and openness among the community towards HIV issues, thereby reducing stigma and discrimination against PLHIV.¹¹

Another factor that supports the sustainability of the program is the independence of the peer support groups by developing economic businesses. They play an essential role in supporting PLHIV, not only in health aspects but also in economic strengthening. Two peer support groups in Belu Regency and Yogyakarta Municipality have started to develop creative economic ventures to ensure program sustainability and reduce dependence on external funding, such as producing herbal oils and merchandise. Peer support groups with their businesses do not need to continue relying on financial assistance from other parties or the government. The income from these businesses can be used to fund their operations, such as mentoring PLHIV, referrals to health services, and advocacy. Some PLHIV also experience discrimination in the world of work, making it difficult to get formal employment. The members and PLHIV who engage in entrepreneurship can have a stable source of income.

Another critical factor in supporting the program’s sustainability is the innovative development of the PLHIV health monitoring application (MONTOV), which Pita Merah Jogja Association uses to support ARV adherence digitally. This application aims to assist PLHIV in monitoring ARV therapy adherence digitally, while supporting the effectiveness of technology-based health services. The app is designed to remind PLHIV not to forget to take ARVs through daily notifications. High adherence minimises the risk of drug resistance and progression of HIV to more advanced stages. The app also serves as an educational medium, providing information on ARV side effects, a healthy lifestyle for PLHIV, and overcoming challenges in long-term treatment. Health workers can also reduce direct visits and focus more on patients who need special attention in health services. Peer support groups can be more efficient in assisting PLHIV, reducing the need for in-person visits that often require additional transport costs. Automated reminders and digital monitoring allow more PLHIV to be consistent on ARV therapy, reducing the number of Lost to Follow-Up (LFU) or patients who stop treatment.

Good Lessons

-

Direct involvement of PLHIV in the PLHIV-friendly continuum of care service workshop and the development of the monitoring tools can provide input as needed to produce it. Continuum of care services only follow the Ministry of Health standards and include additional service indicators that are friendly to PLHIV.

-

The outreach to LFU PLHIV conducted by the community health centres, involving the administrators of the peer support group, yielded optimal results. Directly involving PLHIV by sharing experiences and reinforcing them resulted in changes in understanding and behaviour in PLHIV’s adherence to treatment and increased family support.

-

The direct engagement and meeting of government officials at the local level with PLHIV can open awareness and foster concern for PLHIV and HIV and AIDS control in general. This is also a strategy to reduce stigma and discrimination against PLHIV.

-

The SALT method, which explores the communities’ potential and strength and formulates action plans based on the results of SALT visits, is an effective strategy for proposing activities and budgets related to HIV and AIDS to the village or sub-district government.

-

The AIDS care community has a strategic role in scrutinising and proposing the budget at the village and regency levels, as they have adequate awareness and knowledge of health issues, especially HIV and AIDS. Peer support groups, one of the core stakeholders in HIV and AIDS control, also have a direct interest in government budget allocation related to this issue. The increased capacity of the AIDS care community and peer support in conducting budget policy advocacy can boost their confidence in proposing the budget at the village and regency levels.

-

Capacity building for health care workers is conducted to support the continuum of care services according to the Indonesian Ministry of Health standards. This involves the latest knowledge and skills related to HIV and AIDS, including clinical management, use of new technologies, and understanding of evolving treatment protocols.

Cross-sector Issues

There are still cases of gender-based violence against women living with HIV

Gender-based violence (GBV) remains a significant challenge in the implementation of HIV and AIDS control programs, especially for women living with HIV. This violence can be in the form of physical, psychological, economic, or social violence, which further worsens their health and welfare conditions. Improved gender responsive services are needed so that women living with HIV can access safe, equitable, and inclusive health services. Women living with HIV are often doubly stigmatised, both because of their HIV status and because of social norms that limit women’s roles in society. They are usually blamed for HIV transmission, even when they are victims of unfaithful partners or injecting drug users. Many women with HIV experience violence from their partners, especially when they disclose their HIV status. They may be forced to leave their homes, lose rights to their children, or be denied economic support from their partners. Many HIV health services do not consider women’s specific needs, including protection from gender-based violence. Health workers are often inadequately trained to handle HIV and GBV cases in an integrated manner. Women living with HIV who experience GBV usually have no source of income, making it difficult for them to exit dangerous relationships or seek appropriate treatment.¹²

Programs still need to ensure that HIV services are accessible to people with disabilities, both in terms of infrastructure and inclusive health services.

People with disabilities often face challenges in accessing health services, including HIV and AIDS services. ese barriers are not only physical but also include social stigma, lack of disability-friendly information, and limited inclusive health workers. HIV control programs must integrate the principles of inclusion and accessibility so that no individual is left behind in HIV prevention, care, and treatment efforts. Many health facilities do not have disability-friendly accessibility, such as ramps for wheelchair users, consultation rooms with appropriate facilities, or communication aids for the blind and deaf. Some health facilities do not provide HIV information in suitable formats, such as braille or sign language, making it difficult for people with disabilities to understand HIV information. Many health workers have not undergone specialised training in working with patients with disabilities, often struggling to communicate or provide personalised services. People with disabilities sometimes face discriminatory treatment because they are not considered to be at high risk of HIV, even though they may be infected through various routes, including sexual violence or unprotected relationships. People with disabilities living with HIV are doubly stigmatised, both because of their disability and because of their HIV status. Society often assumes that they are not sexually active, so the issue of HIV among people with disabilities is frequently overlooked in public health campaigns. Most HIV education programs are text-based or based on standard visual media, which makes it difficult for people with visual or hearing impairments to access.¹³

Ghanis Kristia

References:

[1] Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2012). Guidelines for Comprehensive HIV-STI Services. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia.

[2] Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2022). Regulation of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Indonesia No. 23 of 2022 concerning the Control of HIV, AIDS, and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia.

[3] Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2020). National Strategy and Action Plan for HIV and AIDS Response 2020-2024. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia.

[4] Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2013). Regulation of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Number 21 of 2013 concerning HIV and AIDS Prevention. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia.

[5] Indonesian AIDS Policy. (2016). The Role of Peer Support Groups and Improving Their Quality.

[6] Perwira, I., Praptoraharjo, I., Hersumpana, Suharni, M., Sempulur, S., Pudjiati, S. R., & Dewi, E. H. (2016). Case Study: Integration of HIV & AIDS Policies & Programs into the Health System in Indonesia.[7] Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. (2024). Assessment of Health Human Resources in HIV Programmes in Indonesia: Optimising the Availability, Quality, and Performance of Health Workers to Scale Up and Support Client-Centred HIV Care. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia.

[8] Indonesian AIDS Policy. (2016). The Role of Peer Support Groups and Improving Their Quality.

[9] Sistiarani, C., Kurniawan, A., & Hariyadi, B. (2019). Analysis of the Role of the Application of AIDS Care Community on Cadres in Karangtengah Cilongok

[10] Rianto, A. (2024). How to Reduce Stigma and Discrimination. Equal.Id.[11] Suharni, M. (2014). HIV and AIDS Response Funding Policy. Indonesian AIDS Policy.

[12] National Commission on Violence Against Women. (2019). Policy Brief on Women with HIV: “The Cycle of Sexual Violence and Vulnerability to the Right to Life.” Jakarta: National Commission on Violence Against Women and Children.

[13] Pramashela, F. S., & Rachim, H. A. (2022). Accessibility of Public Services for Persons with D i s a b i l i t i e s i n I n d o n e s i a . F o c u s : J o u r n a l o f S o c i a l W o r k , 4 ( 2 ) , 2 2 5 . https://doi.org/10.24198/focus.v4i2.33529